What fishes in the ocean, is the size and shape of a yam, and has the flight agility of a rock? The threatened marbled murrelet of course! The marbled murrelet is an ocean-going bird in the auk family (puffins are also auks) that flies inland to nest and fledge its young and is extremely hard to study, as we were about to find out.

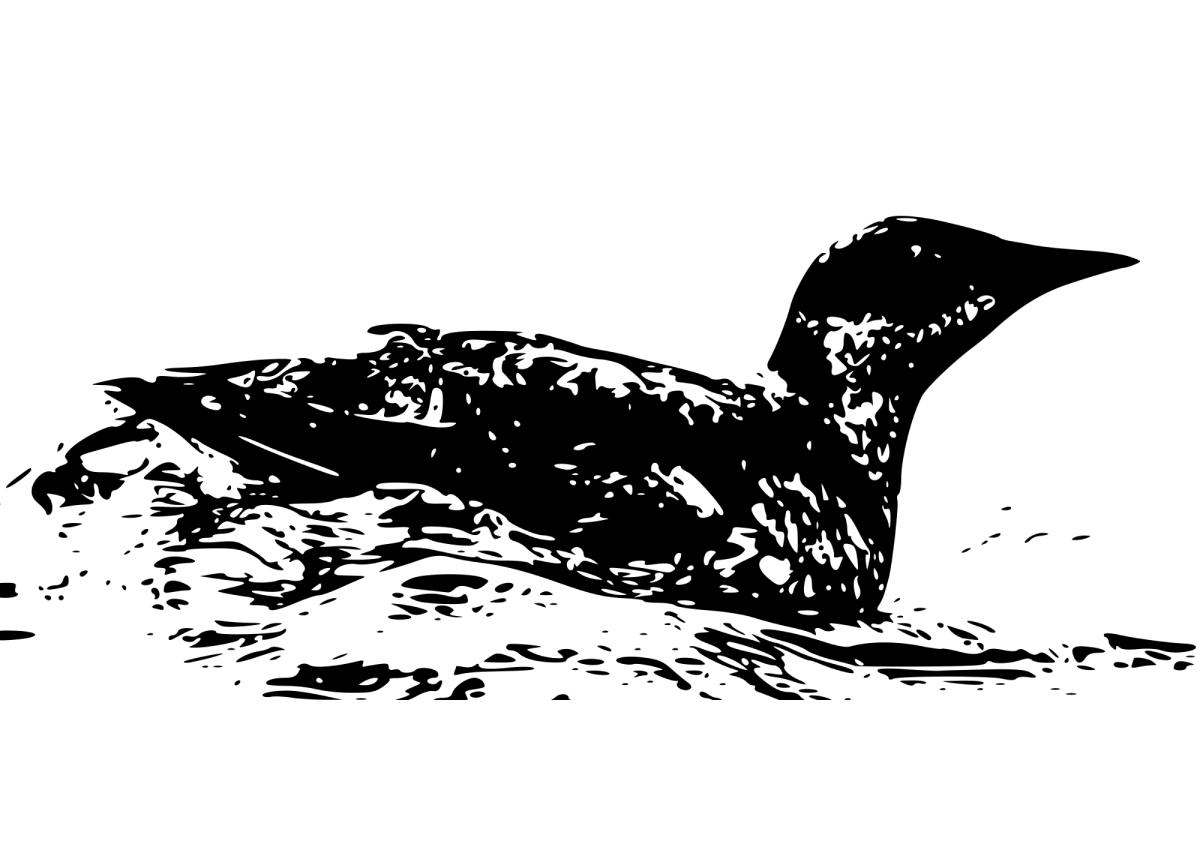

Figure 1. A breeding adult marbled murrelet. Drawing based on a photo from AllAboutBirds, by Russell Kramer

To help a threatened animal you need to know its life history. Where are its critical weaknesses? Is it limited by food, nesting habitat, or something else? Information to demystify the murrelet life cycle has been hard-won and remains slim. This elusive bird was first described in 1789, yet where it nested remained a mystery until 1974, when a climber found a speckled chick with webbed feet in the crown of a large tree (see chick pic). Since then, we have yet to acquire reliable information on the most basic elements of its life cycle, despite considerable effort.

Chick pic. Murrelet chick on a branch doing its best to look invisible. Photo is reproduced with permission from Aaron Allred. Click this link to see a video of this murrelet chick in the wild!

“So Keith, how many nests have you found since you’ve been here,” I asked.

“I’ve been here 25 years and have probably found about 10 nests, and I try something new each year,” he replied. That is a shortened version of his reply, Keith Benson, a wildlife biologist for Redwood National Park and our guide on this expedition, likes to tell lengthy stories in his uniquely quirky brand of intonation and entertaining style of all things park related. “This is going to be our last attempt, I’ve pulled all the strings to pull, and this is the last funding we have for murrelets…people are all excited about the Humboldt Martin now, so that is where the money is.”

“What about camping under the trees and trying to locate them that way?”

“Yep, tried that, doesn’t work”

“What about catching them at sea, fitting them with antennas and tracking them with telemetry”

“Yep, tried that, doesn’t work, they disperse too far.”

“What about, what about, what about…”

“…Yep, tied that, and that, and that.”

Perhaps some background is due. The marbled murrelet spends most of its life at sea eating fish except to rear chicks in the canopy of ancient forests. The female lays one egg that is 30% of her body mass once a year. Imagine a lemon inside a yam (…yum, if you like yam n’ eggs that is). Murrelets do not make nests, instead relying on their offspring to do so by spinning in a circle and defecating into a mounded ring. These nests smell something special because the chicks are fed an exclusive diet of regurgitated fish. The parents leave pre-dawn each morning and fly up to 60 km to forage in the ocean. They return at dusk, leaving the chick to do its best to look invisible.

On a good day the parents’ morning commute looks like this (Figure 2, left), but most of the time it looks like this (Figure 2, right) except in the dark. Heavy coastal fog often blankets the canopy so murrelets tend to key in on emergent trees with large recognizable features. They need large-diameter branches and platforms created by snapped trunks on which to balance their nestless egg. They also need open approaches because they fly really really fast (they’ve been clocked > 100 mph) and without much lateral control. Big platforms with open flyways only occur in big old trees, hence their reliance on old forests (Figure 3).

.jpg)

Figure 2. What a difference a day can make! Fogless murrelet commute (left) and a normal commute (right). Photos: Russell Kramer

.jpg)

Figure 3. A murrelet nest hidden on a large branch in a redwood tree showing the approach fly way behind it. The tree model to the right shows the location of the nest in the tree crown. The nest is approximately 8” across. Photo: Russell Kramer

Most nest trees are located when hikers report speckled eggshells on the ground. A climber, usually my field partner on this trip, Jim Spickler1, then ascends the tree to have a look. But this year is different; this year Keith is pulling out all the stops. Not only are we searching in the stronghold of the southern population of the marbled murrelets, Prairie Creek State Park but Keith has hounds on the trail! Literally! In the spring, a team of dogs were trained on the smell of a closely related auk using eggshells from a zoo. In the early summer the dogs were set to work huffling and snuffling under the sword ferns for eggy evidence of shell shards.

We arrived in November after any chance of disturbing an active nest, to search 14 giant redwoods in 7 days. Keith now had a hit list of trees identified by the dogs and trees with known nests from past work. These latter trees were included because camera traps have shown murrelets returning to the same site in different seasons and there was a chance they might return again.

As Jim ascended into the mid-crown of the first tree, we heard him on the radio: “Hey guys, I found one!” I was jazzed to find a nest of my own, but Jim’s early luck waned and most of the good structures looked like this (Figure 4, right).

Figure 4. Jim Spickler of Eco Ascension Research and Consulting about to ascend into the first tree of the trip. An empty nest site that was previously occupied and is now unused. Note the epiphytic leather fern. Photos: Russell Kramer

As we neared the end of the tree hitlist, our expectations were being set straight. Despite finding ample habitat, including a fire cave tunneling all the way through a tree (Figure 5), we had only discovered nests in two trees. Jim had even searched one spectacularly large and complex tree for three hours in the rain with no luck (Figure 6). Keith then decided to take us on a walk to a tree that an employee had seen an eggshell at the base of the same year. This tree had a high probability of success. Little did we know that physics was quietly conspiring against us.

Figure 5. Fire crept 60’ into this tree and likely hollowed out a decay pocket, creating a tunnel. Right is a view through the tree, and left is a photo taken from within the tree looking out at the forest beyond. Photos: Russell Kramer

Figure 6. This magnificent tree was searched for hours in the rain with no luck. Photo: Russell Kramer

After a 1.5 mile walk, Jim prepared his crossbow (we use crossbows to launch a line into the trees). We carefully scouted a location on a steep slope for him to get a shot. He aimed, and…schwabam! The bow let off a strange noise and the projectile trailing out line only went a fraction of the distance to the first branch. The bow sting had popped off the bow just when fortune looked brightest.

.jpg)

Figure 7. Jim and Keith on the trail of the marbled murrelet. Photo: Russell Kramer

This may sound trivial, but it is not. We use a compound bow whose limbs exert an outward force of at least 300lbs each. The only way we can draw it taught is from the camming pulleys on either limb that give us mechanical advantage. To restring such a bow, you need a specialized bow press. After some prolonged scalp scratching (2hrs) we came up with a dicey solution. Using high tensile strength cord, we pulled the bow limbs back just enough to shove two sharpened sticks into the cams to release the tension on the bow string.

“Don’t worry Jim, those sticks ain’t broke, just badly bent,” I joked, misquoting one of my favorite country songs,* Which wasn’t really that funny because if they broke while we both worked to slip the bowstring over the cams, the full force held in the limbs could rake the string over our forearms, or pinch a finger off, or worse. We tenuously slipped the string over the cams, and both sighed a nervous exhale of relief as the sticks crackled but held.

Figure 8. Jim showing off our sharpened stick solution. These sticks used to be straight…please oh please hold strong! Photo: Russell Kramer

It was Jim’s turn to climb, so after a perfect shot into the tree he ascended. A short time later we heard the radio. We got another one! This was our final tree and an auspicious end to a lovely fall trip.

Figure 9. Ascending into the last tree. The light rays and turning vine maple leaves were good omens! Photos: Russell Kramer

So, what does it take to find a murrelet nest? We found three nests from the dedicated effort of two expert climbers in one week of hard work. But this hides the reality that finding the trees to search was the culmination of decades of experience and the use of scent dogs. The dogs proved useful, allowing us to locate more nests than we would have otherwise, but were not a definitive solution. Many trees they keyed in on did not have a nest. This could be because the egg was predated before a chick could make its fecal nest ring (Figure 10) or because we missed them in our search. We were told that the dogs do not show false-positives, so they definitely smelled something fishy, but perhaps not fishy enough for a successful fledging.

Figure 10. Murrelet eggs are often predated by jays, crows, and squirrels which are more common around campgrounds. Photo: Peery lab University of Wisconsin

Federal agencies like the National park Service are mandated by the Endangered Species Act to do what they can to provide for viable populations of endangered species. In the case of the marbled murrelet, this requires considerable expertise, time, and knowledge. We hope that in the future dogs in combination with drone-based telemetry technology will allow us to locate more of these elusive birds to learn how we might help. One way to help is to keep camps clean of food scraps that attract corvids (jay and crow family) and squirrels.

The murrelet is not the only threatened or endangered bird in Redwood National Park. In a partnership spearheaded by the Yurok Tribe, the park and tribe will release California condors into the ancient redwood forest where they once soared. Like the murrelet, condors used to roost in gnarly old trees. Unlike the murrelet, their threats are singular and known; they are poisoned by ingesting lead from fragmented bullets in dead animals. Until lead ammunition is banned for hunting (the simplest and blatantly obvious solution) all extant condors must be captured every five years or so and put on dialysis to scrub their blood. Stay tuned…

1 Jim Campbell Spickler is the owner of Eco Ascension Research and Consulting and the director of the Sequoia Park Zoo in Eureka, CA which is home of the acclaimed Redwood Skywalk.

* “I ain’t broke, but I’m badly bent” by Old and In the Way.

Author’s note: The dialog in this post is approximate because they are drawn from my memory of a field excursion in November 2022. All tree climbing referenced in this article was done under a permit from the Prairie Creek State and Redwood National Parks.